Table of Contents

Max Planck was an incredible scientist. Everyone in Germany loved hearing him speak, and he toured the country giving talks about his day. But, his chauffeur, on the other hand, got pretty tired of hearing the same speech day-after-day. So, he finally asked: “Max, can I try giving the speech? I’ve heard it so many times, I’m pretty sure I’ve memorised it”. Max agreed and let the chauffeur give his speech. He took a seat at the front and popped on the Chauffeur’s hat, while the chauffeur pretended to be Max and played the part perfectly. The speech was a success! At the end, a man stood up and asked a question. His response: "that’s such a simple question, I’m surprise you’d even ask… I’ll let my chauffeur answer it."

Now, the point of this story is not about how quick-witted the chauffeur is, but rather than there’s a difference between two kinds of knowledge: the deep knowledge that Max had and the shallow knowledge of the chauffeur.

Where possible, our goal should be to deepen our understanding of a topic, and that’s what I want to talk about today.

🧠 The Meta-learning Roadmap

So the first thing we need to think about is learning how to learn, which basically involves building a learning roadmap. This roadmap helps us to figure out exactly what we need to learn and the best way to learn that stuff too.

In short, before working on anything, we should ask ourselves 3 questions:

1. Why do we want to learn this stuff?

In other words, what is our motivation.

This could be extrinsic, meaning we’re motivated by the potential reward we can get from doing well in our studies, such as getting a first class degree. Or it can be intrinsic, meaning we’re motivated because the task is personally rewarding to us, such as learning the thing simply because we enjoy it.

There’s no right or wrong motivation type, but knowing what motivates us keeps us going especially when things get hard.

2. What do we actually need to learn?

Here we want to break down our subject into all the stuff we need to learn and build a high-level overview of what we’re going to be learning in the coming weeks or months.

To do this, get out a piece of paper and write down all the topics and sub-topics we’re going to need to learn. This gives us a neat picture of what they key things are that we need to learn and how each new piece of information/knowledge fits into the wider picture. This is particularly important as we learn best when we associate new knowledge with the stuff we already know.

For example, if someone tries to teach us 1 + 1 = 2, but we’ve got no idea what numbers are, we can’t learn. It’s impossible to do the calculation. We need to be able to associate the symbols with numbers in order to solve the equation. We need to make an association in order to learn.

3. How do I learn it?

Now we know what we need to learn, we need to come up with a plan of how to learn it all.

One way we can do this is to find people who’ve already gone through the process and pattern our own strategies after the methods that worked for them. So, reading this article, for example, should give you a few ideas on how to structure your learning. But make sure you have a look around on YouTube or speak to other people who’ve already gone through the learning process too – getting as many data points as possible will help take your learning to the next level.

♒️ The Flow State

By now we should have a good idea about how we’re going to go about learning the stuff, so now we need to actually start.

The problem I’ve found when we start learning anything is actually focusing on the task at hand. For some reason we’ll do anything but do the work, even if we know it’s irrational. The solution, then, is to have strategies to confront 3 main obstacles:

1. Procrastination – the 10 minute rule

As you know, it’s way too easy to fall into an infinity pool like scrolling through twitter, browsing instagram and the like. But, a really simple trick to stop ourselves from procrastinating and start working is to use the ’10 minute rule’.

It’s super simple: If I’m finding myself procrastinating from something I have to do, I tell myself that I’m just going to do it for 10 minutes. No more, no less. Just 10 minutes. And usually, when I make a little bit of progress, this gives me enough momentum to keep going and before we know it I’ve done a ton of work.

2. Distraction – precommitments

Our environment, the difficulty of the task, or our own emotions can all get in the way of our learning. So, ideally, we’d design our learning space to optimise our concentration on the task.

One way that works nicely is creating what Nir Eyal calls ‘pre-commitments’, which just tells us we should remove a future choice that may distract us. Like, if we know we’ll be tempted to open social media when we work, then we should find a way to block those apps while we work. Or, if our phone is the distraction, we should commit to putting the phone in another room and stuff like that.

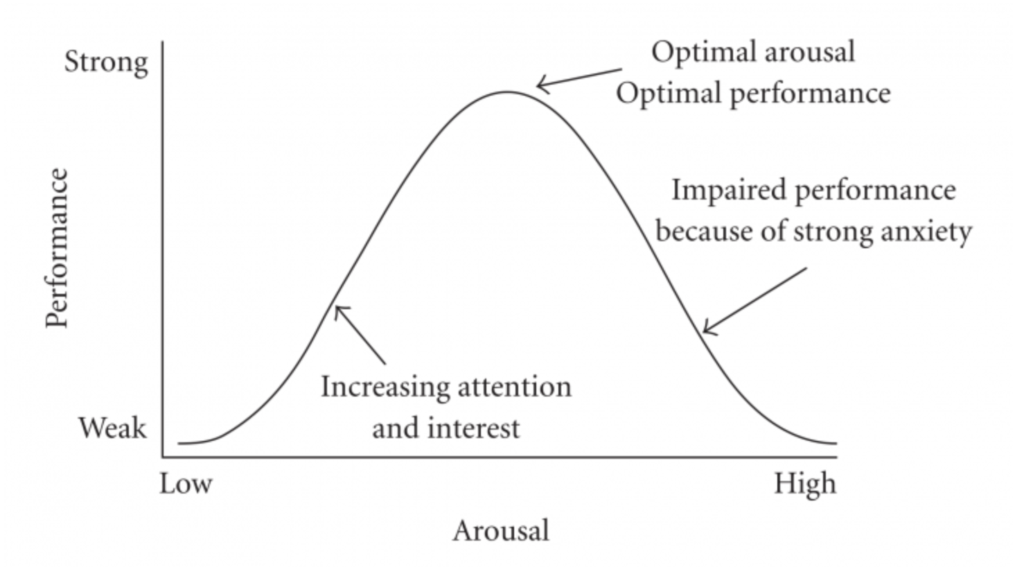

3. Optimisation – arousal

Yerkes-Dodson Law says that we perform better with increased stress or pressure, up to a certain point. Obviously there are a load of factors that influence this, but the point is that we need to make sure we’re appropriately ‘aroused’ (lol) to do the work.

For example, if we’re trying to learn something from a textbook, we’ll have more success doing it in a quiet environment (low arousal) than a noisy one (high arousal). But, if we’re a pro athlete, a slightly higher-stress environment is more appropriate. So, we need to make sure we optimise our focus depending on what arousal level is best for us.

🤹 Deliberate Practice

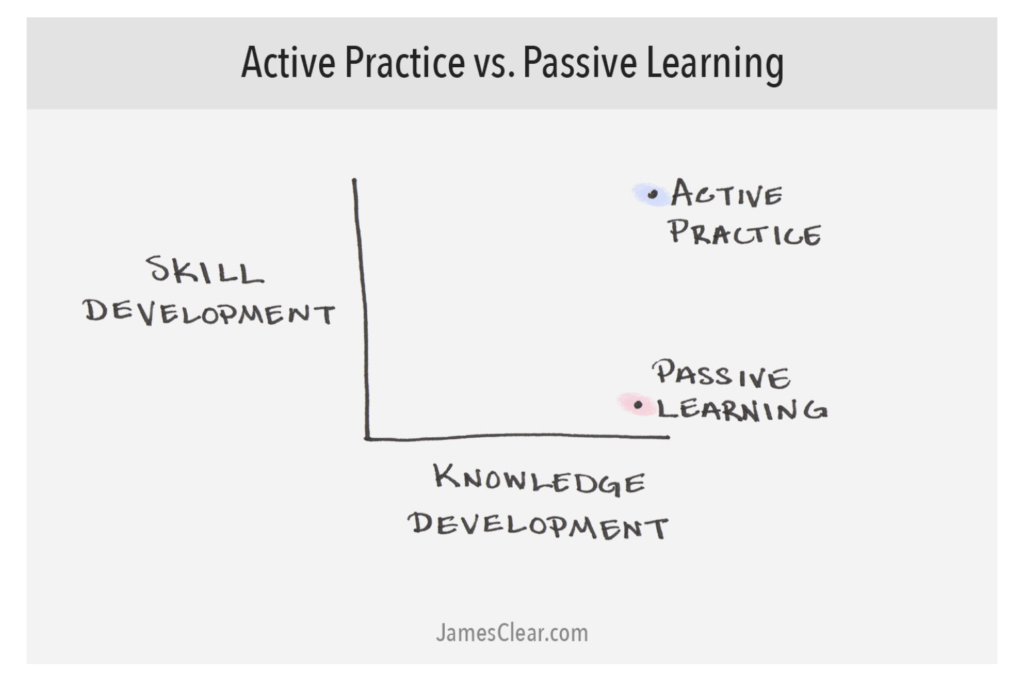

At this point we should be pretty good at getting on with our work, but what is the best way we can actually use that time? The key is to optimise our learning for active practice over passive learning.

Sure, there’s no avoiding the theory and the textbooks when we’re learning something, and starting with this stuff is usually the best place to start when building a solid foundation of knowledge. But, if we really want to deepen our understanding of a topic we need to switch to ‘active practice’ as early as possible.

Like, let’s say our goal is to get stronger. We can research the best textbooks on bench press technique, but the only way we’re going to build strength is to actually practice lifting weights.

So, what techniques can we use to optimise our learning for deliberate practice?

1. Create projects

Projects are more valuable than lectures and textbooks because they force us to create a result, which needs us to have a pretty deep understanding of the thing we’re trying to learn. For example, if we’re doing our degree, we should get involved in something like the Innocence Project, which will force us to have a pretty good understanding of criminal law as we’re working towards a proper and serious result: to overturn wrongful convictions.

2. Challenge yourself

This is related to the previous point, but we want to use what we’re learning in an environment that demands the highest proficiency level of the skill we’re learning. So, if we’re trying to master an instrument, maybe try out for the university orchestra. Or, if we’re trying to get better at international law, maybe we’d try out for the Jessup international mooting competition. All this stuff pushes us to learn more and understand the stuff more deeply than everyone else.

3. Combinatory play

This is all about taking two or more seemingly unrelated topics or skills and getting really good at both of them, as this can help boost our creativity, lead to new ideas, and think in a different way about what we’re trying to learn.

For example, I decided to studying maths at some point during my law degree and I found that this helped me think and structure my law essays more logically. So, really our deliberate practice doesn’t necessarily have to be that focused on our specific learning goal, as there’s a certain level of cross-over between every skill we learn.

“Originality often consists in linking up ideas whose connection was not previously suspected,”

W. I. B. Beveridge (in the fantastic 1957 tome The Art of Scientific Investigation)

⛏ Drilling

As we study, we’ll probably notice that we’re not good at everything. And that’s okay. The important thing is we have a process for isolating those weaknesses and concentrating intensively on them. Doing this helps to unlock areas of learning that are stopping us from making decent progress and deepen our overall understanding of the topic.

So, if we use law school as an example, I had a few topics I was pretty weak in. Internal Markets in European Union law was one of them. Like, if you’d asked me about article 34 and 35 of the TFEU I’d have been like “oh God, I have no idea”. And so, when it came to studying efficiently for my exams, I knew that I had to drill the things I was weakest on. So, I just spend a whole day basically focusing on that one topic

Doing this helped me to plug the topic as an area of weakness and now I’m pretty good at talking about it.

So, the question I keep asking myself when I’m learning something is “if the exam or test were tomorrow, what topic would I be least happy about coming up?”. And then I just study that topic.

This is great because whenever we’re learning it’s super tempting to do the stuff that we’re familiar with or good at and not face up to our weaknesses. But, really, learning only happens when we’re trying to fix our weaknesses and operate at a certain level of difficulty. So, if we want to maximise our learning and deepen our understanding of something, we want to really hone down on the weak links and focus on those.

🧩 The Encoding Process

One mistake a lot of people tend to make when learning is that they forget that the whole point is to actually retain the information. In other words, we want to encode that information into our brain so it’s easy to recall when we need to use it.

There are broadly three things we need to do to make this happen:

1. Self-testing

Reading, highlighting, underlining, and those passive learning techniques are super ineffective and won’t actually help us to retain the information. Instead, the large majority of our study time should be spent asking ourselves questions to recall the information we learn, using things like flashcards.

The process of forcing our brain to retrieve information on its own, without having our notes in front of us, both helps us to commit that information to memory but also helps clarify what we don’t know. In other words, we pinpoint our weaknesses and know that’s something we need to spend more time on.

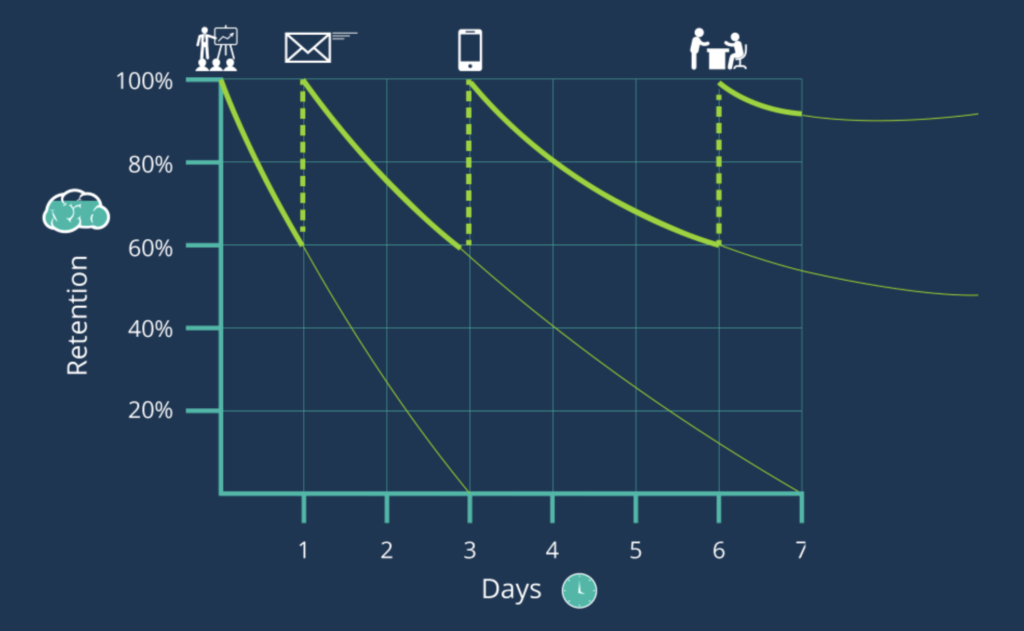

2. Spaced repetition

When we begin learning anything, we should space out the learning of that topic over a number of different study sessions. For example, if we’re learning how to play a song on the piano, it’s better to devote an hour to the task every couple of days than to learn the whole song in one go.

This is based on something known as Ebbinghaus’ forgetting curve, which I’ve talked about loads before – this tells us that the more we revisit and refresh our memory on a topic the stronger our neural pathways will be, meaning it’s easier for us to recall that information more proficiently over time.

3. Overlearn

Basically, when we’re learning something we actually want to try and learn it in more depth than we necessarily need to. For example, it’s easy to be given the lecture notes and textbook on a certain topic, understand that stuff, and leave it there. But the best students always go above and beyond the books. They look for the interesting journal articles, they understand the grey areas, and seek to find the reason why things are how they are. That’s how we should approach any skill we want to master.

📣 Feedback

After some time we’ll be pretty good at whatever it is we’re learning, but there’s always goigng to be room for improvement. This is why we need feedback, because it gives us the opportunity to find out if what we’ve learnt – and how we’ve applied it – is correct.

The best way to get feedback is to put ourselves in real-world situations where others can tell us what we need to work on. For example, if we’re trying to improve our essay writing, write more practice essays and give them to our lecturers or post them online. The more exposure we can get to our work the more varied the feedback we’ll receive and the better we’ll get.

Importantly, the type of feedback we want is corrective feedback. Basically we want people to tell us what we’re doing wrong and how to fix it. This is why it’s probably better to get feedback from an expert or, at least, someone who’s more advanced than us so they can give us the appropriate next steps to improve our thing.

Whenever you’re getting feedback, I always recommend asking two questions:

- “In what ways do you see me holding myself back?” – people who know us well can help expose our blind spots and point out habits, behaviours, or other stuff that may be holding us back from progress. Like, when writing an essay they may notice that we consistently structure our essays poorly and they can give us guidance to address that.

- “On a scale of one to 10, how would you rate (BLANK)? – we want to ask others to evaluate different aspects of the skill we’re working on. So, if we’re aiming to write persuasively, we may ask them to rate how convincing out writing is and why.

So, always ask for feedback because it always helps to get another pair of eyes on our progress.

🤓 Intuition

Finally, and to bring things around full circle, we only really know a subject when we develop a deep, detailed understanding of the ideas and principles we’re trying to learn.

Broadly, there are two ways we can deepen our knowledge of a subject:

1. Let yourself struggle

We should always face up to the hard parts of what we’re trying to learn snd not shy away. Like, if we can’t wrap our head around a certain legal concept, we need to keep working on the problem until we’ve solved it. This leads to a more proficient understanding of the topic.

The way I like to do this is as follows: if I’m faced with something I’m struggling to wrap my head around, I break it down into more manageable steps. So, if I can’t wrap my head around ‘assault’ in tort law, I’ll always go back to the definition – “an intentional act which directly causes the claimant to reasonable apprehend the application of unlawful force” – and try to understand each component part of that definition.

2. Challenge your understanding

We should regularly question ourself to avoid the cognitive bias that leads us to overestimate our knowledge. So, always ask “Do I understand this well enough to explain how it works?”.

Often I think I know something in my head, but as soon as I try to verbalise that thought I realise there’s a ton of gaps in my understanding. So, the more we can try to explain concepts and ideas to other people, even when we think we know it well, the more we’ll begin to challenge our understanding and figure out whether or not we really do know the topic.

👨💻 Planck Knowledge vs Chauffeur Knowledge

As a final thought, remember that there’s two types of knowledge.

One is Planck knowledge, the people who really know. They’ve paid the dues, they have the aptitude.

And then we’ve got chauffeur knowledge. They’ve learned the talk. They may have a big head of hair, they may have fine temper in the voice, they’ll make a hell of an impression. But in the end, all they have is chauffeur knowledge.

Real knowledge comes from putting in the work.

Any fool can know. The point is to understand.

Albert Einstein