Table of Contents

At uni I managed to get over 70% in every law essay I wrote.

This isn’t meant to be a brag, but an interesting reflection given that I didn’t write these essays like most people. Instead, I built an efficient, reliable and systematic way to approach essay writing, which I want to share with you.

It’s broken down into 5 stages.

🎯 Stage 1: the goal

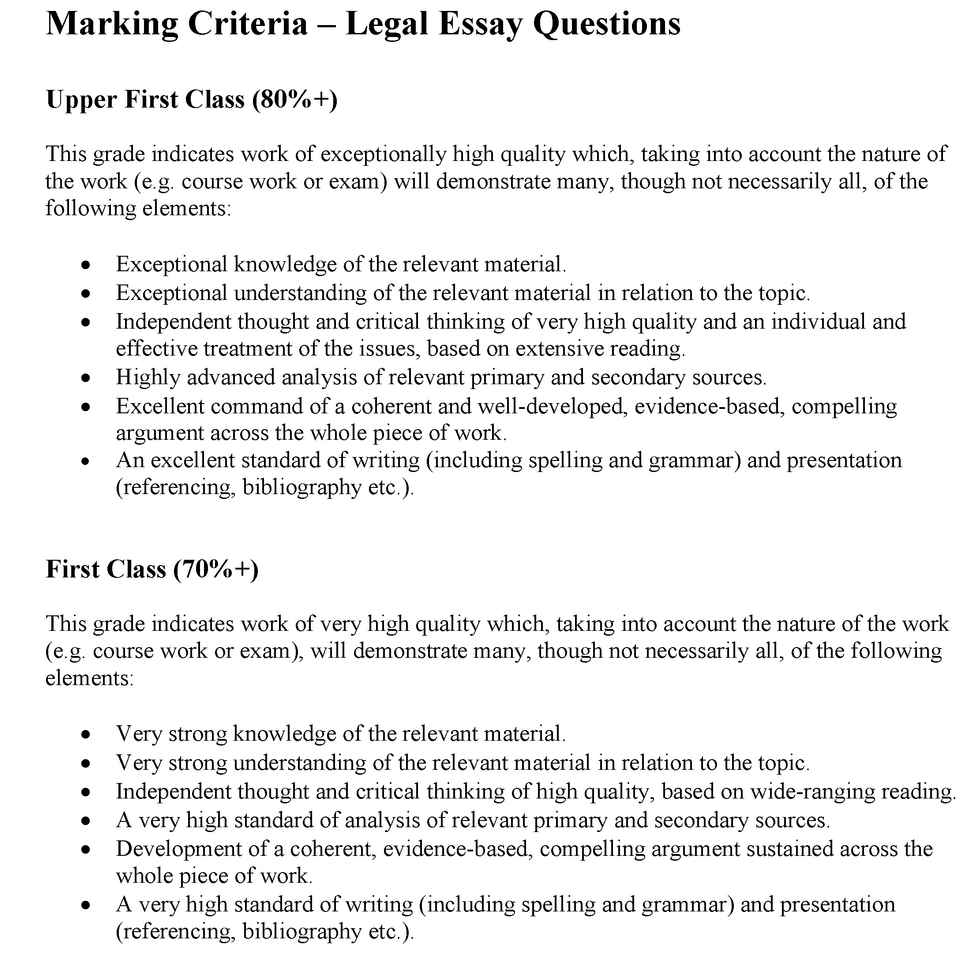

The first stage of everyone’s essay writing process should begin with the goal in mind, which for most of us is probably to get a first class result.

Now, I’m always surprised by how many people have literally no idea what it takes to get a first, when every single university has a set criteria telling us what they’re looking for. And it’s these criteria that we need to constantly keep in mind when we’re planning and writing our essays, as this is what the lecturer will use to mark our work.

So, broadly, what are these criteria?

Well, I think most lecturers would agree that the basic elements of a first class essay include 4 things:

- Close attention to the question and answering that question with breadth and accuracy, with no or almost no significant errors or omissions

- Detailed knowledge of the topic addressed as well as a deeper understanding of the context in which that topic exists and the less obvious points of law

- Presentation of theoretical arguments concerning the subject, significant critical analysis of relevant sources, and thoughtful personal perspective on the debate, supported by relevant evidence

- A well-developed and compelling argument coupled with an excellent standard of writing.

In short, we need to understand the question, research the topic well, have an opinion on the given topic, and write a convincing argument.

With this goal in mind, broken down into these 4 steps, it becomes ridiculously easy to work through our essays in a systematic way that ticks off all the criteria of a first-class piece of work.

All we need to do is work through them one-by-one, starting with understanding the question.

🤔 Stage 2: the question

The key to success with our essays is the ability to address and answer the question we’re given.

Now, this may seem like stupidly obvious advice, but it’s crazy how often students will screw up an essay just because they’ve ignored what the question is asking, misinterpreted the question, or decided to answer a completely different question because it’s easier to do so.

For example, take the question ‘what is a constitution?’. Many students will go down the path of outlining the nature and sources of the British constitution. But, this is not what the question is asking. Nor is the question asking us to list the different categories of a constitution. Instead, we should provide a number of definitions of a constitution, such as “a document containing the rules of government”, the “fundamental and supreme law of the state”, and so on. Then, we can use this information to identify the central features of a constitution.

The problem is that we’re so eager to demonstrate our knowledge, we end up answering the question in a really general way to ‘prove how smart we are’. But, this just won’t work.

So, what should we do?

The very first thing I like to do when I begin thinking about the question is to write it down on a piece of paper, fully deconstruct it, and make sure I know exactly what type of question has been set.

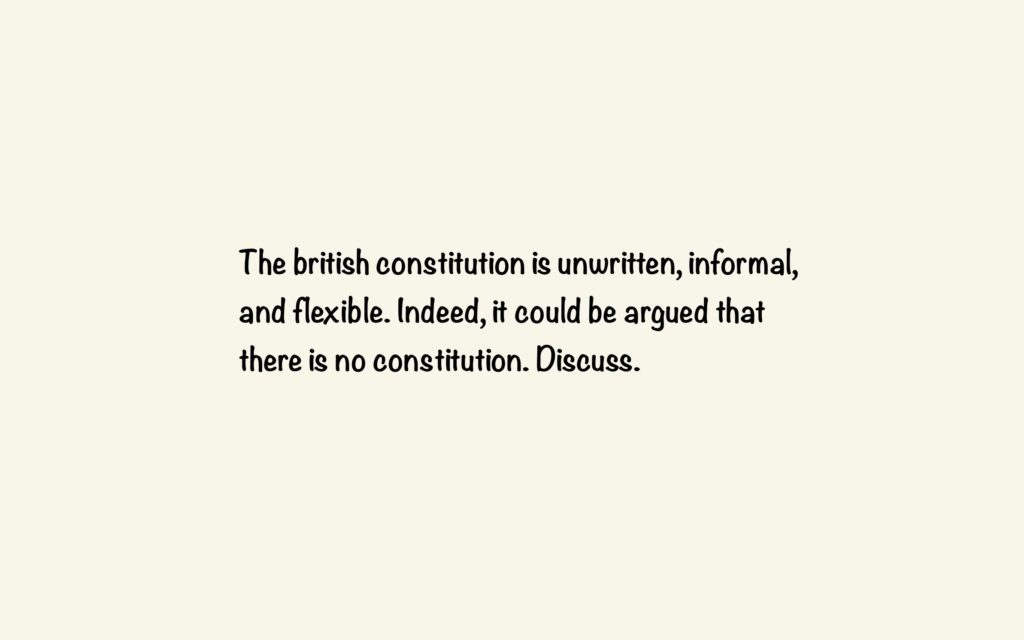

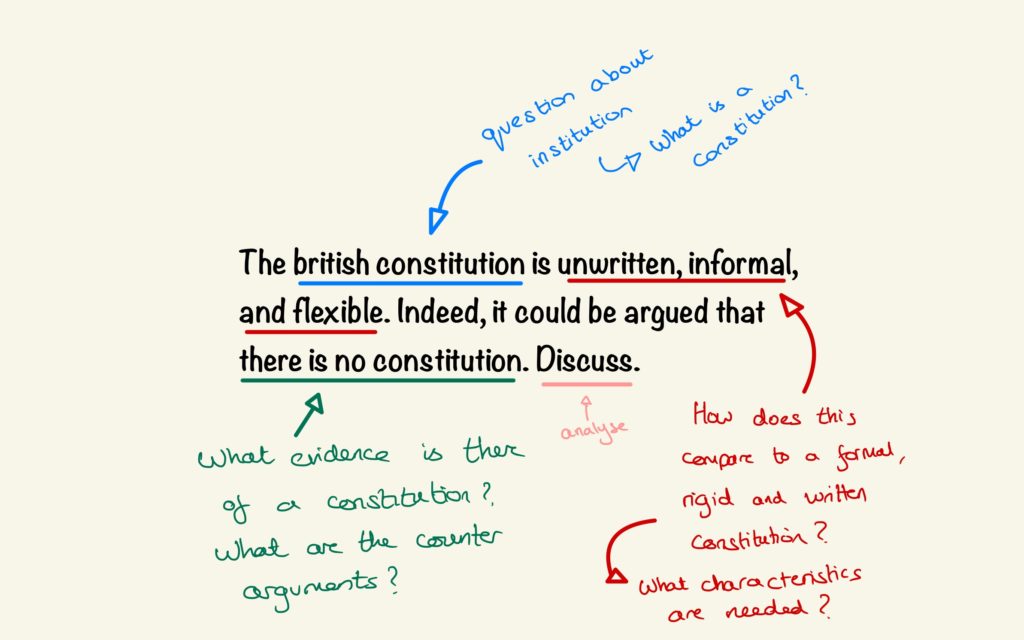

Like, let’s say we’re given the following question:

First, I’ll think about the type of question that’s being asked. Some questions relate to substantive legal topics (contract, tort, criminal law), legal concepts (e.g. the law, the rule of law, justice) or institutions (e.g. constitutions, legal systems, courts). And then there are those questions that are more descriptive and analytical.

This question is specifically asking us about our understanding of a particular institution (the British constitution) and for us to analyse whether or not it actually exists.

So, the way I’d probably approach this question is to:

- Define what a constitution is and what it should contains – as a side point, always be aware of the vague or grey concepts that the question is asking you to tackle, like justice, rule of law, constitutionalism and so on.

- Then, discuss what is meant by the term ‘unwritten, informal and flexible’ with respect to the British Constitution, comparing it with written, formal, and rigid constitution. I’ll also be thinking here how relevant these characteristics are to the questions of whether a constitution exists. Like, are rigidity and formality necessary?

- I could also provide evidence of the British constitution to argue that it does exist – things like that there’s an established system of government, established principles of constitutional reform, and things like that. But, we need to remember that this is a discussion where we’re analysing the statement. So, we’d also be looking to provide evidence that the British constitution doesn’t exist. Things like a lack of a fundamental, supreme law + sovereignty of Parliament as opposed to sovereignty of the constitution.

Hopefully, by deconstructing the question in this way, we begin to build a high-level picture of what the essay is going to look like, giving us a solid starting point to begin our research, where we deepen our understanding of the topic.

🔺 Stage 3: the research (the Minto Pyramid Principle)

At the stage, we’re ready to do some research.

But, before we dive into the books, there’s a bit of preliminary work we need to do to make sure we’re not wasting our time reading useless material.

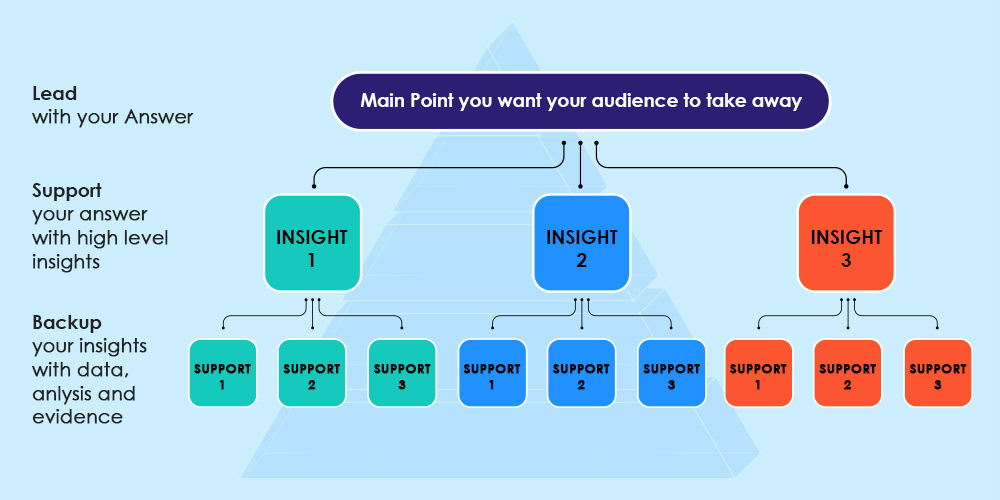

Basically, we need to create a new document in word, or wherever we want to collect our research, and structure that page in a way that helps us to properly answer the question. And the way we do this is by using the Minto Pyramid Principle:

The idea here is that ideas should always form a pyramid under a single thought. So, the single thought is the thesis or the answer to the question at hand, and then underneath that we’ve got a number of supporting arguments, which, in turn, are backed up with different pieces of evidence

With this in mind, then, we want to structure our page with the same headings as we find within the Minto Pyramid. That way, whenever we’re doing our research, we essentially just slot in the information into it, and gradually a fairly comprehensive essay structure should start to form.

One thing I always try to do before I properly start to research the question is to write out my thesis. I may not 100% know how I’m going to answer the question, but I usually have a vague position that I want to argue, so I use that as my starting point that guides my initial research.

Then I move on to doing the actual research.

For example, if I were researching the question ‘Critically assess the impact of the Human Rights Act 1998 on the British Constitution’, this is the general approach I’d take:

- I’d start by reading my own notes and relevant chapter in a couple of different textbooks. This gives me a solid grasp of the law and helps me to identify the central issues: why the Act was passed and how it changed the law; its central provisions and leading cases, and, more specifically, the basic constitutional concerns and dilemmas that the Act has impacted on.

- I’ll also access and read the central provisions of the Act to ensure it’s all consistent with my knowledge and with what the textbooks said.

- By now, I’ll probably have a good idea of the main points that I want to make, so the process from here is to flesh them out, find evidence and critical analysis with further reading

- I’ll then try to find some more specialist texts on the topic e.g. here I’d look at more detailed stuff on the Human Rights Act or constitutional reform, which will help me to identify specific concerns and discuss them in detail.

- Finally, I’ll locate and use a number of journal articles dealing with the main issues, which will help me to critically analyse with confidence. Before, accessing and reading any primary sources that provide me with a fuller understanding of the essay title and the issue – things like judgements of leading cases decided under the Act; provisions of the European Convention of Human Rights; and other stuff like that. This will all help me to find detailed supporting evidence and criticisms of the main points I want to make.

At some point I’ll create a more detailed article on this process, but once I’ve done the research the goal now is to inject some critical thoughts into the structure.

🕵️♂️ Stage 4: the analysis

The analysis stage doesn’t take that long, but it’s the big difference between a second class essay and a first class essay, so it’s worth giving it some thought.

By now we should have a pretty decent understanding of what other people think from both sides of the argument we’re exploring in our essay. Given this, we should have a broad idea of which side of the fence we sit, which hopefully supports the thesis statement we made at the start of the process.

The plan now, then, is to go through all the counter-arguments that cropped up during our research phase and add our own thoughts about why those counter-arguments can be rejected or why they lack weight.

Here, we’re not expected provide the same level of knowledge or insight as a professor, but we are expected to appreciate the argument they make and make relevant observations + criticism about their work. In fact, we can be fairly clumsy with our criticism, as long as we’re demonstrating a willingness to engage critically with academic opinion and the issue at hand, we’re going to be rewarded for doing so.

Now, I’m not going to go into too much detail here as I’m going to write a separate article on how to do proper critical analysis in law at some point. But the underlying point is that we should always finish our research stage by thinking about the topic and really try to figure out what we actually think about the question.

🤓 Stage 5: the essay

Okay, so we’re now ready to begin writing the essay itself and we should have a solid starting point if we’ve followed every stage so far.

Introduction

With the introduction, our goal is to show we understand the question and the legal issues – it should be brief, demonstrate we know what the issues are, and, as far as possible, clearly state our thesis. A mistake a lot of people make is to make the introduction as mysterious as possible, leaving the answer to be revealed in the conclusion. But, this isn’t a great way to write. Why? Because it’s so much easier for the marker to be told what we think upfront then be given evidence for why we think that way, than to be given the evidence first before being told what that evidence means at the end of the essay.

This is probably the hardest part of the essay writing process and I’d honestly spend like 25% of my time trying to get that right because it sets the tone for the rest of the essay and really emphasises the point I’m trying to make.

Main Body

Then once we’ve sorted the introduction, we’re literally just going to go through each of the supporting arguments we wrote in our research stage and put it into full sentences. Basically, we’re dealing with each point in turn, addressing all aspects of the question and providing relevant legal authority for each point. This is an unbelievably quick process and takes ALL the pain out of writing essays because the hard work was done earlier.

Conclusion

Finally, we wrap things with our conclusion. This should just contain a summary of the issues dealt with along with your own concluding remarks that actually answers the questions. Again, put some decent amount of time into this because sometimes the marker will look at this before they check out the rest of the essay to make sure you have properly addressed the question and the main issues that ought to be addressed.

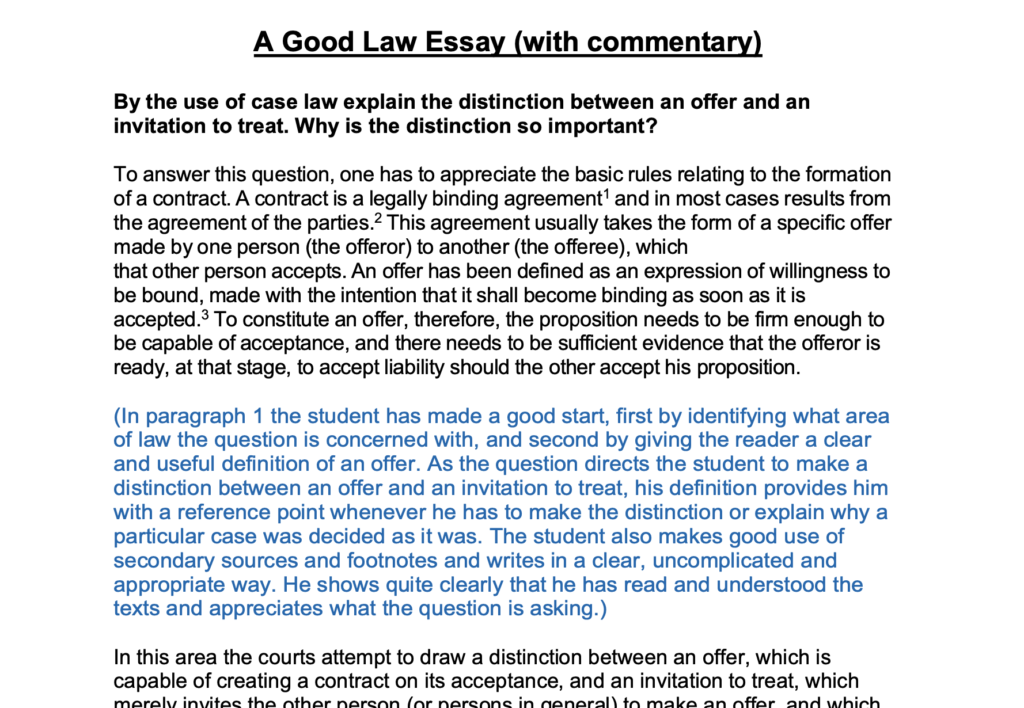

So, yeah, that’ pretty much it – if you want to know what a good law essay looks like with full comments on why, then make sure you download the exemplar for FREE by signing up to my weekly newsletter:

Once you’ve confirmed your email, you’ll be directed to the template. Feel free to unsubscribe from my newsletter at any time! 😁

Here’s a sneak peek of the exemplar essay: